Hey everyone, welcome back to My Weird Prompts. We are coming to you from our usual spot here in Jerusalem, and today we are tackling a topic that literally hits home for us.

Herman Poppleberry here, and you are right, Corn. It is literally right outside our window. Our housemate Daniel actually sent this one in while he was out and about, and it is a fascinating look at how the very walls around us are governed. He was asking about mixed-use zoning, which is basically the fancy urban planning term for having shops, offices, and apartments all in the same building or on the same block.

It is one of those things you do not really think about until you are trying to find a coffee shop within walking distance or, on the flip side, trying to sleep while a bar is thumping music downstairs. Daniel mentioned that while we used to separate everything for health reasons, modern planning is pushing for more density. But how do we actually decide what goes where?

It is a massive shift in philosophy. For the better part of the twentieth century, the gold standard was something called Euclidean zoning. It is named after a court case, Village of Euclid versus Ambler Realty Company, back in nineteen twenty-six. The idea was simple: keep the smoky factories away from the houses, keep the busy shops away from the quiet streets. It was all about segregation of use. But we have to be honest, Corn, it was also often used as a tool for social and racial segregation, keeping certain types of housing out of certain neighborhoods. Now, in twenty twenty-six, we are realizing that when you separate everything, you end up with these sterile ghost towns at night and massive traffic jams during the day.

Right, because everyone has to drive from the residential zone to the commercial zone. It creates those tech parks Daniel mentioned, where it is bustling at two in the afternoon and then looks like a post-apocalyptic movie set by eight in the evening. But moving away from that creates a lot of friction. I mean, Daniel’s point about not wanting to live above a nightclub is a very real concern for most people.

You have hit on it, Corn. That is the tightrope walk of modern zoning. How do you get the vibrancy of a Paris street corner without the headache of a loud neighbor? It really comes down to how a city categorizes its uses. Most cities have these massive tables of permitted uses. They break it down into categories like retail, professional services, light industrial, and heavy industrial.

And I imagine the professional services part is the easy win, right? Like Daniel said, an architect’s office or a real estate agency is a dream neighbor. They are quiet, they work nine to five, and they do not bring in huge crowds of people at three in the morning.

Right. Those are often permitted by right in mixed-use zones. But when you get into food and beverage, things get complicated. You have to look at things like venting for kitchens, trash management, and of course, noise. A lot of cities now use performance-based zoning instead of just saying yes or no to a business type.

Performance-based? So instead of saying no bars, they say you can have a bar as long as it stays under a certain decibel level?

That is right. Or they might say you can have a restaurant, but your trash pickup has to happen in a specific internal bay so it does not block the street, or you need a certain level of soundproofing in the floor between the commercial and residential units. It is about the impact of the business rather than the label of the business. New York City actually just finished implementing their City of Yes initiative, which updated these exact kinds of rules to allow small-scale clean manufacturing, like micro-breweries or three-D printing shops, to exist in residential areas as long as they meet strict environmental standards.

That sounds great in theory, but I can see why Daniel mentioned the bureaucracy in Israel. It feels like getting those permissions here is like trying to move a mountain. We see it all the time in Jerusalem, where a beautiful old building sits empty for years because the zoning does not allow for a small cafe on the ground floor.

Israel is a unique case because the system is so centralized. Most planning decisions go through these regional committees, and the TABA, which is the local building plan, can be incredibly rigid. If a building was zoned as purely residential forty years ago, changing even one floor to commercial use can take years of legal battles and public hearings. However, with the new light rail lines opening up across Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, the government is finally forcing through more flexible zoning along those corridors to ensure they do not just become transit deserts.

It is funny because Jerusalem actually has some great examples of mixed-use working well, even if the paperwork was a nightmare. Look at parts of Jaffa Road or even some of the older neighborhoods like Rehavia. You have these little grocery stores or bookshops tucked into the bottom of apartment buildings. It gives the neighborhood a soul.

That is so true. And that brings us to the global examples Daniel was curious about. Paris is the one everyone points to, especially with their push for the fifteen-minute city. The idea is that everything you need for daily life—work, food, health care, education—should be within a fifteen-minute walk or bike ride from your front door.

I love that concept, but Paris has a huge head start, doesn't it? Their architecture was designed for this centuries ago. Those Haussmann buildings with the high ceilings on the ground floor and apartments above were built for mixed-use before it even had a name.

You are spot on. The ground floor, or the rez-de-chaussée, was always intended for commerce. But what is interesting is how they manage it today. Paris uses very fine-grained zoning. They might protect certain types of businesses, like artisanal bakeries or bookstores, to make sure a neighborhood doesn't just become a row of bank branches and clothing chains. They realize that a diverse mix of businesses is what makes the street feel alive.

That is a second-order effect people often miss. If every ground floor is a bank, the street feels dead after five p.m. even if it is technically mixed-use. You need the stuff that draws people out at different times of the day.

Right. And then you have a place like Tokyo, which has probably the most flexible zoning in the developed world. In Japan, zoning is handled at the national level, and it is much more about what you cannot do than what you can. You can pretty much put a small shop or a quiet cafe anywhere. They have about twelve different zones, but even in the most residential ones, you are allowed to have a small home office or a tiny shop.

And does that lead to the noise issues Daniel was worried about? Or do they have a different way of handling the social friction?

It is a mix of culture and clever design. In Japan, there is a big emphasis on not being a nuisance to your neighbors, but they also use a lot of vertical separation. You might have a building where the first three floors are retail, the next five are offices, and the top ten are apartments. By the time you get to the residential units, you are far enough away from the street noise that it is actually quite peaceful.

That makes sense for high-rises, but what about the mid-rise stuff we see more often in Europe or even here in Jerusalem? How do they solve the noise problem when you are literally six inches of concrete away from a restaurant kitchen?

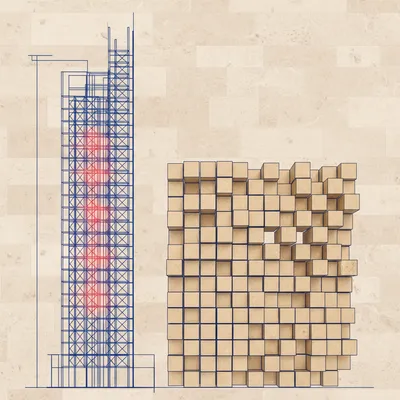

That is where the engineering gets really interesting. Modern mixed-use buildings use what they call floating floors. You basically build a floor on top of specialized acoustic pads or springs so that the vibrations from a kitchen or a sound system do not travel through the structure of the building. You can also use staggered studs in the walls and triple-pane glass for the windows. In some of the newer mass-timber buildings being built in twenty twenty-five and twenty twenty-six, they are using cross-laminated timber with specialized acoustic mats that can actually outperform traditional concrete for sound dampening.

It sounds expensive. I am guessing that is one of the reasons developers sometimes push back against mixed-use. It is much cheaper to just build a box of apartments than it is to build a complex sandwich of different uses with all that specialized soundproofing.

It is definitely more expensive up front. But the long-term value is often much higher. Mixed-use buildings tend to be more resilient. If the residential market dips, you still have commercial income. If the retail market struggles, the apartments are still full. Plus, from a city's perspective, mixed-use is a tax goldmine. You get more property tax and business tax from the same footprint of land.

And you save on infrastructure. You do not need to build as many massive highways if people are walking to the store. But I want to go back to Daniel’s concern about privacy. Even if you solve the noise, there is the issue of having strangers in your building. In a traditional apartment block, you know everyone who walks through the lobby. In a mixed-use building, that lobby can feel like a public square.

That is a huge design challenge. The most successful mixed-use projects usually have completely separate entrances. The residents have their own lobby, often on a side street or around the corner, while the businesses face the main thoroughfare. You want the vibrancy of the street, but you want a private threshold for your home.

I remember seeing this in London, actually. They had these new developments where the ground floor was all glass and shops, but the residents had a secure entrance that led straight to an internal courtyard. It felt like two different worlds. Once you were inside the courtyard, you couldn't even hear the buses on the main road.

That is the goal. It is about creating layers. You have the public layer, the semi-public layer, and the private layer. When zoning is too restrictive, it prevents those layers from overlapping in a healthy way. You end up with these islands of activity separated by oceans of empty parking lots.

Which is just what Daniel was complaining about with the tech parks. I have worked in those places. You go there at noon, and it is a struggle to find a seat at the one sandwich shop that serves five thousand people. Then at six p.m., the whole place feels haunted. It is a massive waste of space and resources.

And it is bad for our mental health, honestly. There is a lot of research showing that walkable, mixed-use environments lead to lower rates of loneliness and higher levels of social trust. When you see the same shopkeeper every morning or run into a neighbor at the local cafe, it builds a sense of belonging that you just do not get in a suburban office park.

It is that third place concept. We have our home, our work, and we need that third place—the cafe, the library, the small park—to feel like part of a community. Mixed-use zoning is basically the legal framework that allows those third places to exist where people actually live.

That is a key point. And it is not just about the nice-to-have stuff like cafes. Think about aging in place. If you are eighty years old and you can no longer drive, living in a purely residential suburb can be a death sentence for your independence. But if you live in a mixed-use building with a pharmacy and a grocery store downstairs, you can maintain your autonomy for much longer.

That is a powerful point. It makes the city more inclusive for everyone, not just the young professionals who want to live above a bar. But how do we get there? If the current system is so bogged down in bureaucracy, how do we transition to this more fluid model?

A lot of cities are moving toward what they call form-based codes. Instead of focusing on what happens inside the building, the code focuses on how the building looks and how it relates to the street. It says the building has to be a certain height, it has to have windows facing the sidewalk, and the entrance has to be accessible. As long as you meet those physical requirements, the city is much more flexible about whether you have an office, a shop, or an apartment inside.

So it is less about micro-managing the business and more about ensuring the building contributes to a good streetscape. I like that. It trusts the market to figure out what the neighborhood needs while protecting the public’s interest in having a nice environment.

That is the idea. And we are seeing some cool experiments with this. In some parts of the United States, they are bringing back the corner store by creating special small-scale commercial permits for residential neighborhoods. It allows a house on a corner to turn its ground floor into a tiny market or a coffee shop, provided they follow strict rules about noise and hours of operation.

I can imagine the neighbors might still be nervous. There is always that fear of the unknown. If I bought a house in a quiet area, I might not want a coffee shop opening up next door, even if it is a nice one.

That is the classic NIMBY—Not In My Backyard—tension. But what often happens is that once the shop opens and the neighbors realize they can walk two minutes for a fresh croissant and a chat, they become its biggest defenders. The convenience and the social value usually outweigh the minor increase in foot traffic.

It is about changing the perception of what a business is. It is not just a commercial entity; it is a neighbor. When we think of it that way, the zoning becomes less about policing and more about facilitating relationships.

That is a great way to put it. And if we look at the historical context, for most of human history, this was the norm. The idea of living miles away from where you work or where you buy your food is a very recent, and arguably very weird, experiment in human history. We are basically trying to find our way back to a more natural way of living.

It is funny how the most modern, cutting-edge urban planning is actually just trying to recreate what people were doing in the Middle Ages, just with better plumbing and soundproofing.

Ha! You are not wrong. The medieval street was the ultimate mixed-use environment. You had the blacksmith on the ground floor, the family living above, and the apprentice in the attic. We have just traded the blacksmith for a graphic designer and the apprentice for a guest room, but the fundamental human need for proximity remains the same.

So, looking forward, do you think we will see more of this in Israel? Or are we stuck with the rigid TABA system for the foreseeable future?

There is definitely a push for change. The national planning authorities are starting to realize that they cannot keep building sprawling suburbs in a country as small as this. They are encouraging more mixed-use in new developments, especially along the light rail lines in Tel Aviv and here in Jerusalem. The challenge is going back and fixing the existing neighborhoods where the zoning is still stuck in the nineteen seventies.

That seems like the harder task. It is easy to plan a new mixed-use district from scratch, but retrofitting a sleepy residential block is a political minefield.

It is, but it is happening. You see it with things like urban renewal projects where old, crumbling apartment blocks are replaced with modern buildings that have commercial space on the bottom. It is a slow process, but the momentum is moving toward density and vibrancy.

I think Daniel would be happy to hear that, though I am sure he would still be checking the soundproofing specs before signing a lease. It really comes down to that balance. We want the city to be alive, but we also want our homes to be a sanctuary.

And that is the ultimate goal of good zoning. It should not be a barrier; it should be a bridge. It should bridge the gap between our need for community and our need for privacy. When it works, like in those Paris neighborhoods or a well-designed Tokyo street, you do not even notice the zoning. You just notice that life feels easier and more connected.

It is one of those things where if the planners do their job perfectly, no one even knows they were there. You just feel like you live in a great neighborhood.

That is it. And that is why these discussions are so important. Zoning is the invisible hand that shapes our daily lives. It determines whether you spend two hours a day in a car or ten minutes walking through a park to get your groceries. It is a technical topic, but the implications are deeply personal.

It really makes you look at your neighborhood differently. I am going to be walking down the street today wondering about the TABA for every building I pass.

Welcome to my world, Corn. Once you start seeing the zoning, you can never unsee it. You start seeing the missed opportunities and the hidden potential everywhere.

Well, I think we have given Daniel a lot to chew on. It is a complex issue, but it is one that is literally shaping the future of our cities. Before we wrap this up, I want to remind everyone that if you are enjoying these deep dives, we would really love it if you could leave us a review on your podcast app or on Spotify. It genuinely helps other people find the show and keeps us going.

Yeah, it really does make a huge difference. And if you have your own weird prompts or questions about urban planning, technology, or anything else, you can head over to our website at myweirdprompts dot com and send them our way. We love hearing from you guys.

Definitely. We are on Spotify as well, and you can find the RSS feed and a contact form on the website. Thanks for sticking with us through this exploration of the walls around us.

It has been a blast. This has been My Weird Prompts. I am Herman Poppleberry.

And I am Corn. We will catch you in the next episode.

See you then!

Bye everyone.

Goodbye!